CHDs and Adolescents

Adolescents are still in the process of learning how to communicate with their health care providers, as most communication between adolescents and health care providers is mediated through the parents.

Encourage responsibility and self-care

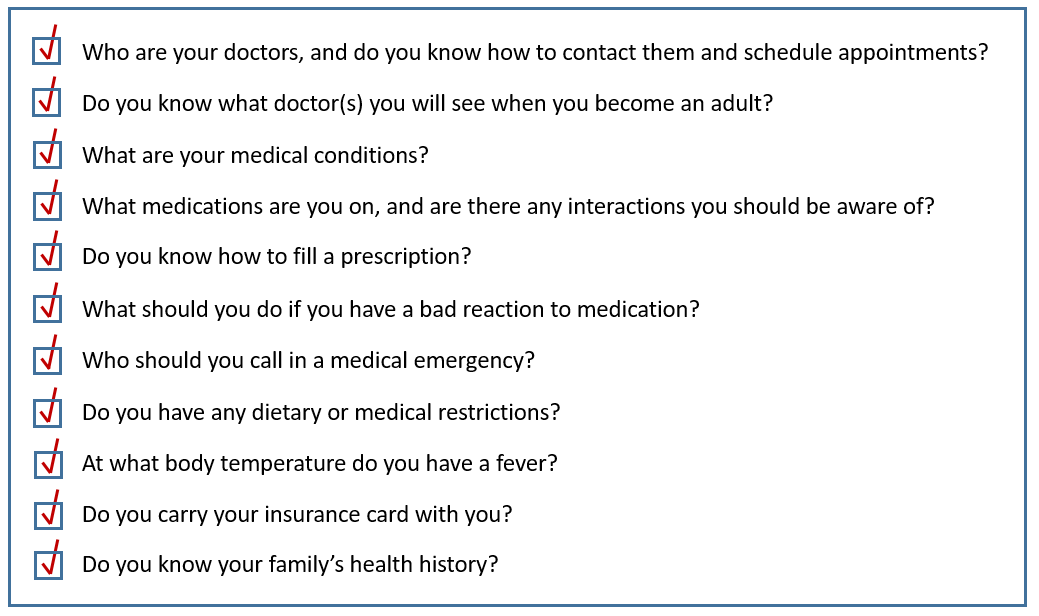

Make sure your child knows all about his/her condition and medical history. Studies show that adults with CHD often do not know much about their heart condition, which can jeopardize self-care. When appropriate, encourage your child to see the cardiologist on his/her own so that they can begin taking control of their care. When needed, involve a health professional such as a social worker, psychologist, or specialist in adolescent medicine with expertise in dealing with teenager issues.

Alcohol, Smoking, and Drug Use

Depending on the type of CHD a teenager has, drinking alcohol may worsen the condition or cause symptoms, like palpitations. Alcohol can also interact with medications. Check with your doctor to know how to proceed regarding alcohol intake.

Smoking results in circulation problems and possibly blood vessel damage. Smoking can have an effect on the drug levels in your child’s body.

Regarding over-the-counter drugs, check with your child’s cardiologist to make sure that there is no risk given his/her condition or other medications.

Talk to your child’s cardiologist about what herbal remedies, if any, are safe to use.

Regarding street drug use, it is important that teenagers be aware of how street drugs can potentially affect their condition – they can increase side effects, introduce new ones, or increase or decrease the effect of heart drugs.

Piercings and Tattoos

People with heart conditions are always at risk of bacterial endocarditis, which is why they must take antibiotics if they are undergoing surgery or having work done on their teeth. Any procedures that draw blood, that includes things like piercings and tattoos, enable bacteria to get into the system.

Sex and Contraception

Young adults with CHD should get information about having sex well before they consider becoming sexually active.

Oral contraceptives (combined estrogen and progesterone) are safe for most young girls with CHDs; however, they are not appropriate for those with cyanotic CHDs, complex disease, or pulmonary hypertension. The concern with oral contraception is that it increases risk of blood clots, so oral contraception should not be used by those at risk for clotting or with high blood pressure (progestin-only contraceptives may be an alternative). Intrauterine devices (IUDs) should not be used if bacterial endocarditis is a risk.

Additional Resources

References

Clarizia NA, Chahal N, Manlhiot C, Kilburn J, Redington AN, McCrindle BW. Transition to adult health care for adolescents and young adults with congenital heart disease: perspectives of the patient, parent and health care provider. Can J Cardiol 2009;25:317-322.

Hetherington R. The teen with congenital heart disease. 2009. The Hospital for Sick Children. http://www.aboutkidshealth.ca/En/ResourceCentres/CongenitalHeartConditions/LookingAhead/TheTeenWithCongenitalHeartDisease/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed February 22, 2018.

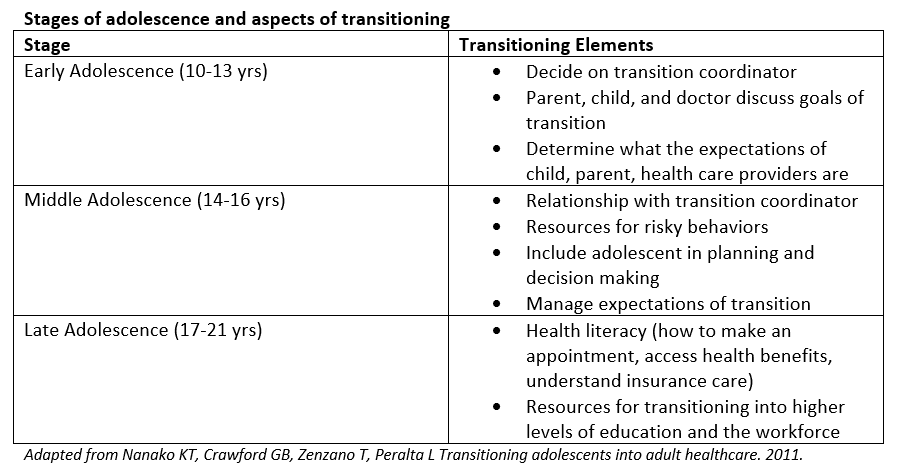

Nanako KT, Crawford GB, Zenzano T, Peralta L Transitioning adolescents into adult healthcare. 2011.

Nye A. Is your teen or young adult prepared to manage his own healthcare?. 2014. Cincinnati Children’s. http://blog.cincinnatichildrens.org/healthy-living/is-your-teen-or-young-adult-prepared-to-manage-his-own-healthcare/. Accessed February 22, 2018.

Sable C, Foster E, Uzark K, et al. Best Practices in managing transition to adulthood for adolescents with congenital heart disease: the transition process and medical and psychosocial issues. Circulation 2011;123:1454-1485.

Wilson DG. Congenital heart disease in teenagers. Paediatrics and Child Health. 2010;21:13-18.